There can be nothing more frustrating in the middle-early days than when sales closes some great deal for, say, $125,000 a year … but you “knew” they could have gotten $200,000 if they just held the line on discounting.

You’d talked to that customer yourself, they were basically already sold (in your mind, at least), they were gonna buy without a doubt … why the heck did we leave $75k on the table? And hey that’s prepaid cash. We could have done a lot with that $75k. Plus next year, we’d get that $75k again. And so on. That rep that just closed that $125k deal, getting high fives all around, ringing the bell? In your mind, she left $300k on the table! (that $75k x 4 years).

You may be right, at a micro level. But the fix — if any — is at the macro level. And odds are, you were actually wrong.

The at first nonobvious thing about discounting is the dynamic:

Sales reps on commission will naturally do 2 things:

- First, they’ll quote at list price. That’s Maximum Commission, after all. But — then …

- Then, at the end of the month / quarter / whatever, They’ll Discount, Ultimately to the Maximum, if Pushed. Because they want to hit their number. Better to get 70% of the original quote and hit my quota for the quarter, than miss my quota this quarter and hope I get 90-100% of that original quote next quarter. At least, 8-9 times out of 10.

- And — the best reps know time is the enemy of deals, and that the shorter the sales cycle, the more deals close. So they use discounts strategically to both bring down sales cycles and increase the # of deals that close. The shorter you can make a sales cycle, the more money you make in the aggregate. You may not believe that empirically if you are lead constrained, but the best sales managers know this is true and align their reps here.

So yeah — that’s what you’d do if you were a successful, experienced rep on commission and quota.

Then, the customers do the following:

- If it’s a true enterprise deal ($50k+ ACV, selling to an enterprise buyer) — they know this. They know the cadence and rough boundaries of discounting. So about 7-8 times out of 10, if the ACV is large enough, and they don’t need it today … they may just wait until the end of the month / quarter, ask for the biggest discount, and sign then.

- Worse, in a true enterprise deal, many buyers will feel ripped off if they don’t get a discount. Even if it’s not their money and not that expensive in absolute terms, many buyers at least don’t want to be ripped off. No one does.

- Even “worse”, they’ll generally send the negotiated deal off to Procurement. Who then is often financially incented to get another discount. Many procurement professionals’ bonuses and comp are tied to part to getting at least X% off the average P.O. sent to them.

Ok, so what do you do?

Well, first note that “Holding The Line” in true enterprise deals doesn’t always work well. It can extend sales cycles. If a discount is one of the best weapons reps have to close this month, if you take that away, sales cycles lengthen. And that puts deals at risk.

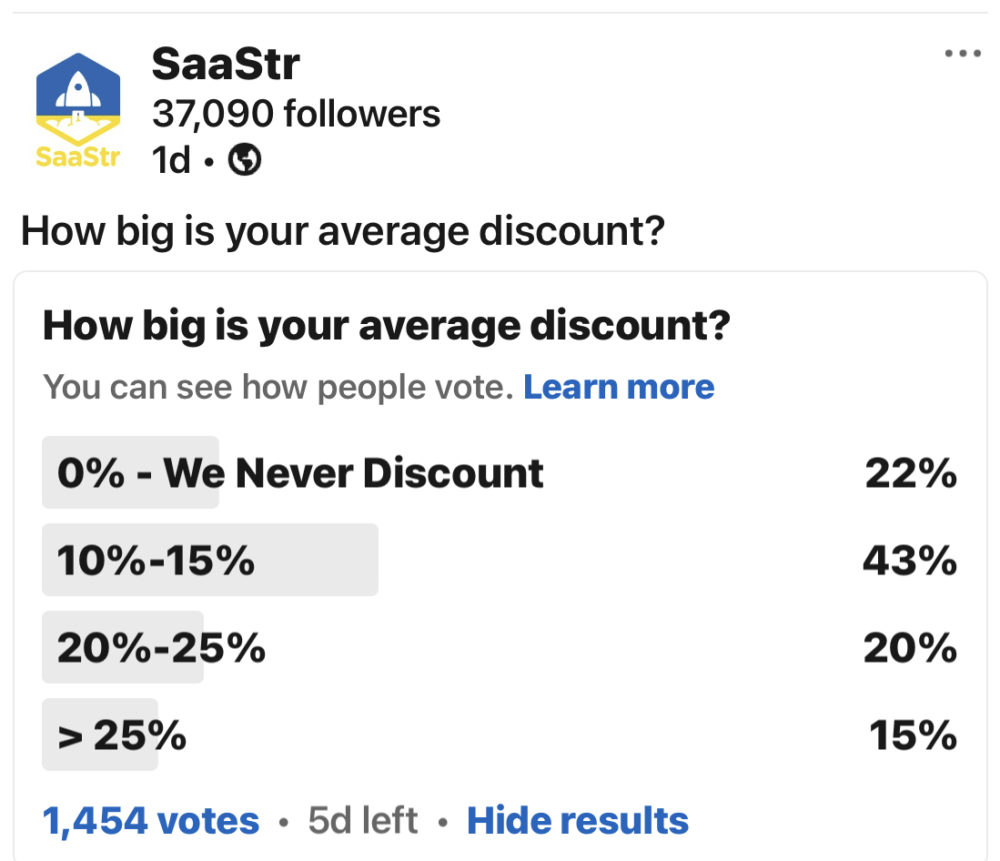

Second, many enterprise customers expect a 10-15-20% discount. If they don’t get it, it will feel “off”. They might even think you aren’t a professional vendor. Even best case, it may confuse the sales process in higher ACV deals.

In smaller deals, customers will still ask for discounts. But if the pricing is transparent and clear on the website, and the ACV is $5k or so or less, you’ll have an easier time holding the line. Especially if you offer one simple discount for prepayment, or something similar, so at least they have a choice.

Net net, people have written books on this stuff. Let me simplify it into a handful of recommendations:

- Control, but don’t eliminate, discounts in larger deals. Put it through a control process so reps have bright lines. You can do that through simple rules at first, and later, through systems like a CPQ system.

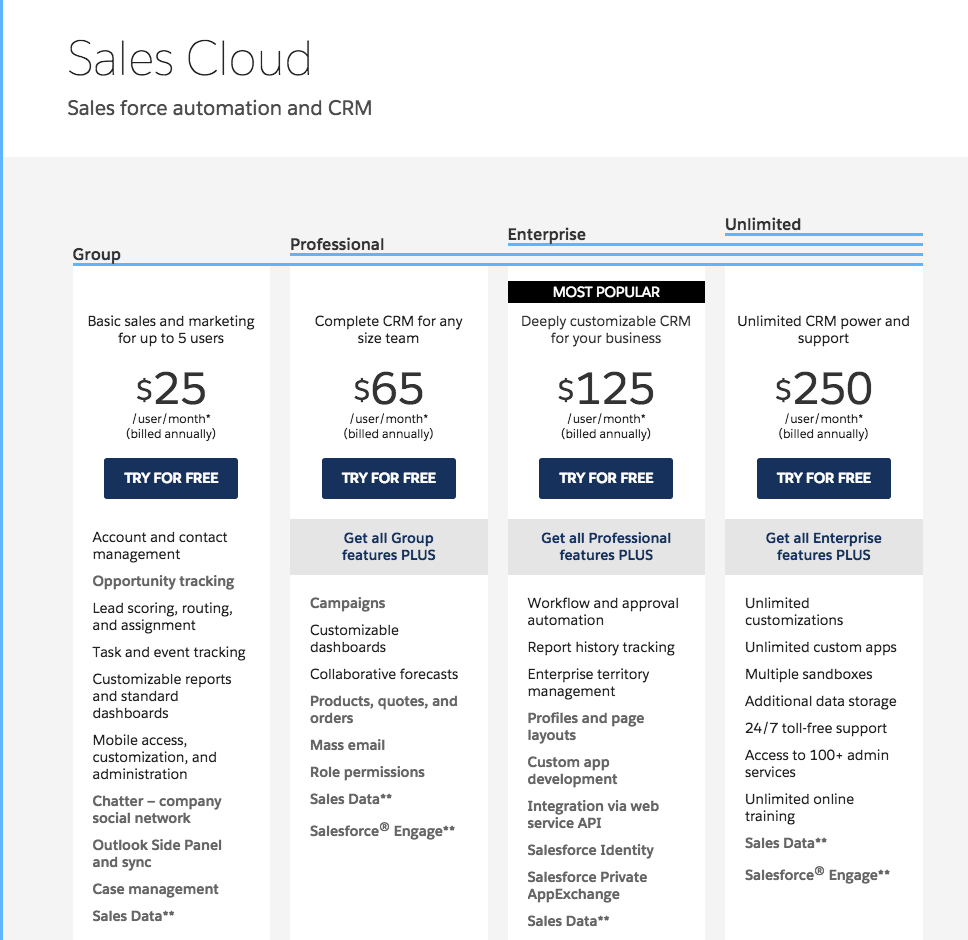

- Segment your pricing so it gets more expensive for the largest customers. And then — mark everything up 20%. If you have transparent pricing, make the prices for the most enterprise tier(s) 20% higher than the yielded pricing you actually model. If you have non-transparent pricing here, do the same thing by marking the first quote up 20%. Even if it’s more expensive than the competition — it’s OK. Pricing is rarely the #1 issue in a competitive deal, and if it is, you’ll hear about it, and the quote won’t lose you the deal. This is why Salesforce does this:

- Automate any discounting — if any — at the low end. The simplest way to do this is again mark prices up 20%. Then, give a 20% discount for annual prepayment. You can see above Salesforce did this, too. Everyone does this in some form or other.

- Model an additional “procurement discount” into larger deals. You may need to give again in procurement. If that’s the case, model it in. Maybe mark the deal up 30% if the deal has to go through procurement. It is what it is. You can’t win here. You have to give procurement an additional discount in many cases. They are often comped on it.

- Finally, once you have a real one — trust in your VP of Sales to work this out and hit her team quota and company ARR commit. If your VPS has to hit the company’s ARR goal (and not just a bookings goal), the two of you will be 100% aligned here. Help out and do all of the above. But be careful of micromanaging. All great VPs of Sales know that discounting is part of the give and take, the psychology of sales. And they don’t want to discount more than necessary, either. Because they own the aggregate number, unlike any individual reps.

Later, when you are really bigger, you can truly optimize this further. For now, don’t let it frustrate you, and most importantly, don’t think you are unique or anything special. Your product is unique and special. Your sales process, including pricing, isn’t.

And don’t try to change the way the world wants to buy, including discounts. Instead, at first, at least, hack the system like noted above.

So you end up where you really wanted to be in the first place.

(note: an updated SaaStr Classic post)