A few years back, a very wise VC asked me what I thought about a small but scrappy competitor in the space of my last company, Adobe Sign / EchoSign.

I told him I didn’t know the company that well, but from what I’d seen, some things might seem appealing. I bet the freemium metrics appeared good, with positive growth and solid conversion rates. I told this VC I bet that while they had no true enterprise customers, they had a few nice silos within some large customers. And I told this VC that while I hadn’t used this particular competitive product directly really, that I’d bet some of it seemed slick. After all, they got to build it more recently.

But — I said I think you should pass, at least for now. If they wanted to go for a Big Unicorn / Decacorn Exit at least. Because I suspected that small but interesting early traction was just bottom-feeding in the market. Not a true disruption in the market.

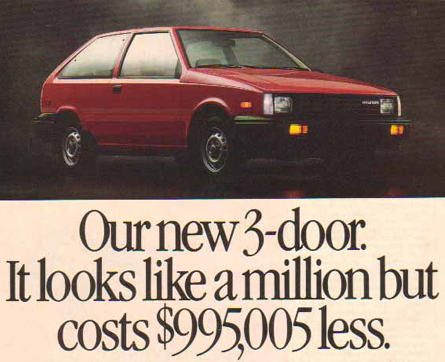

The VC challenged me, and I said I was wrong every day … but I asked him what they were doing that was disruptive. He said this competitor was cheaper.

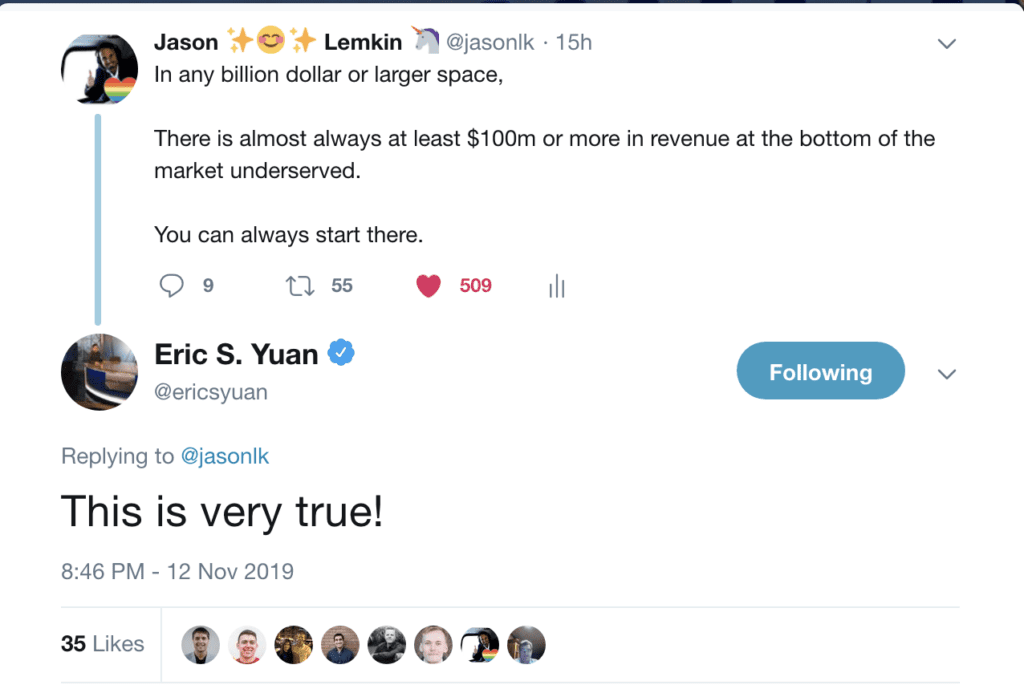

Hmmmm … well, to me, that’s not a bad place to be once a space, a category, gets to $100m+ in total ARR. Cheaper. Because at this scale, there will be room at the bottom. And once a category gets to $1B in total ARR, well even a 2%-3% market share alone can get you to $20m-$30m ARR. A great place to get to.

But that’s not Disruption — in SaaS at least. Not usually.

———-

Sometimes in SaaS, there are natural monopolies. But more often, SaaS categories with significant complexity in workflows and features end up in natural oligopolies.

For a while, it’s hard to tell what’s happening in these oligopolies. But then the leaders break through, achieve Scale, and the outlines become clear. And that takes time, years.

And then … once the total space hits $100m or so in ARR, plus or minus … new scrappy entrants don’t just pop up, they actually get something really going. While new players always sort of popped up in the past, but before, when the space was tiny, they didn’t seem to make any impact. But once the space is large enough … the new players … are able to get some traction, at least a little, and maybe more than a little.

What’s happening?

Well, if you’re the new kid in the $100m+ ARR space, it’s possible you are Disrupting The Big Guys. Maybe.

But it’s more likely something different is happening. Once the players in a new market get pretty big themselves, they’ll ultimately most likely raise prices. Try to increase deal sizes. And focus, at least to some extent, on the higher ROI parts of the business. And at a sales perspective, they’ll move to optimizing revenue per lead, over closing every possible lead.

You get big enough, and it’s even better to let a customer or two go at $100k if you can close the third for $1m. Once sales and marketing gets to be all about the top line, you need to let some marginal customers just go, if for no other reason than holding on price.

And that, among other factors, creates Room at the Bottom. And the bigger the category, oftentimes, the more room.

There are obvious cons at the bottom:

- Harder to raise significant capital. You may be able to raise some, but once $50-$100m has gone into the space, it may be harder for you to do the same if you are just The Cheaper Version. Truly disrupt the leader and there probably will be endless capital available to you. But at the bottom, money is tougher. Having said that, with Cloud so big, as long as you are growing quickly, it’s no longer fatal to VC fundraising to be #3 or #4 in a space. More on that here.

- Harder to Recruit. The great ones want to join the leaders in the space. Fair or not, it’s just a fact.

- You’ll Have to Be Scrappier. With less capital and a tighter team … you won’t be able to spend as much on marketing. You’ll have to develop a very lean sales culture.

- Limited M&A Opportunities, and Very Low Prices. If you’re #3 or #7 in the market, a lot of acquirers won’t even be interested in you. And if they are, it’ll be because you are cheap. Don’t expect a premium. Expect a discount — and fewer dance partners.

But the bottom isn’t all bad. Advantages include:

- Easier to Get Going. Since you’re entering once the space is large enough, you’ll actually get leads if you have a good product. The guys that started earlier, even though they are much bigger today, had it much tougher in the beginning.

- Easier to Innovate. You don’t have 100,000 legacy customers to support. So do some cool things. Take some risks that don’t tie 100% to revenue.

- Opportunistic M&A. OK, if you’re the bottom-of-the-market competition, you may never sell for $4 billion. But the thing is, sometimes certain acquirers want to go cheap(er), and buy a smaller player. They’re not sure the space is worth a big, career-risking investment – yet. They want to experiment. In this scenario, the big players in your space would never get purchased by the Opportunistic Acquirer. But here, a $20m or $30m or $50m, or sometimes even a $200m+ deal if the space is hot, becomes possible. Take limited dilution and that might become appealing.

And of course, play it right, and you can start at the bottom and grow into the higher-priced, higher-market share tier. It’s hard to bank on this if the big competitors are agile enough, but certainly, it happens.

I’m not opposed to Playing at the Bottom of the Market. Just two learnings from my experience. First, don’t confuse initial traction at the bottom with disruption. Know what you are, at least at a given point in time. And if you’re Playing at the Bottom — be scrappy. Don’t overfund yourself. Because there’s gold there too, just most likely rather less of it.

If you’re entering that $100m+ market, with a solid feature set but price as your key initial differentiator — that may be OK. Just Know Thyself, and plan accordingly.

(note: an updated SaaStr Classic post)