A little while back, Harry Glaser sold his SaaS analytics startup, Periscope Data, for $130M. It was a difficult, punishing, and rewarding experience. At a recent SaaStr Workshop Wednesday, he shared a behind-the-scenes look into what this process looks like and five key takeaways for other founders who want an inside look into the process.

The Journey of Selling Your Startup

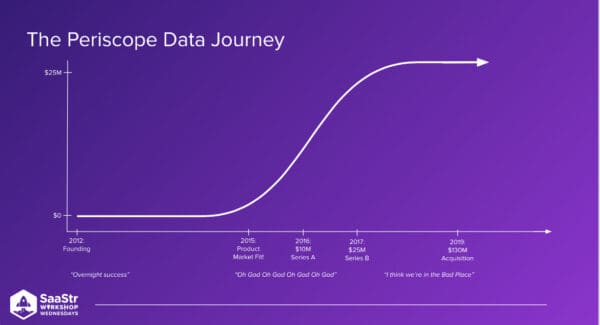

Harry was the co-founder and CEO of Periscope Data, which raised a seed round before finding customers, yet didn’t run out of money before becoming an overnight success 3-4 years later. They grew like crazy when they found product-market-fit and raised a big Series A and B.

When you’re growing fast, everything can feel like it’s breaking constantly, and you’re hiring and rehiring people fast. During those rapid growth years, someone would reach out every once in a while and ask if Harry would consider selling. He always said no.

But then growth flatlined for a couple of years, and it was time to talk about selling. From the start of the company to a couple of years after being acquired, it was about a ten-year journey altogether.

How Does the Classic Bread-and-Butter Startup Exit Happen

This learning isn’t about multi-billion dollar mergers or acqui-hiring. It’s about the $50-$500M bread-and-butter, classic startup exit. A lot happens quickly, and there’s a big information imbalance between you and an acquirer. How do these exits happen? Where do they come from?

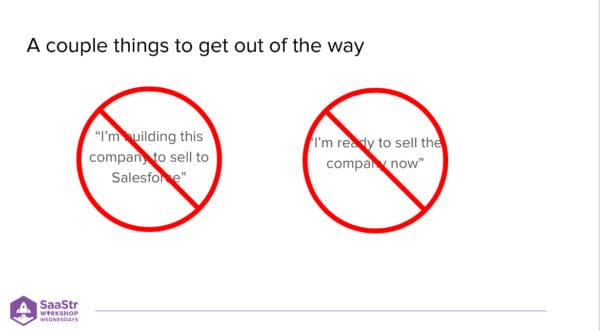

The adage is true that tech companies aren’t sold. They’re bought. You’re positioning the company to grow for the long term and could potentially have a great IPO someday. Or, if you get a great offer and can consider it because it’s not too late.

Lesson 1: Offers Come When They Come

You should grow your company for the long run. If you build a company with the intention of getting acquired and you call up an acquirer, you lose your leverage. You want people to call you because you have a great business.

Who does the acquiring? Most often, you get a call from a function called corporate development. They execute deals, and part of that is having relationships with companies in the space. It’s not a bad relationship to have, but understand that they’re deal executors, not deal creators.

At places like Google or Meta, they’re organized into business units. The VP or SVP of the business unit will be the relationship you want. At a pre- or post-IPO tech company, it’ll likely be the CEO or CPO. These people initiate the big offers. Yes, this is a longer-term strategic play to build relationships with these people, but it could be worth it in the end.

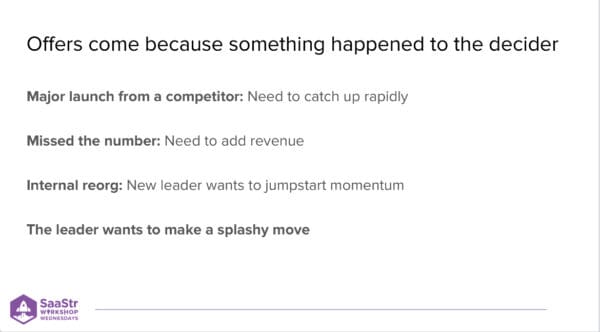

Why Do Offers Come?

If it’s a CEO of a small-compared-to-Google but larger tech company, they’re coming to you because something happened to them internally that put them on their back foot. They may feel behind in where the industry is headed, and they need to make a splashy move to reset the narrative.

Or, maybe they missed a couple of quarters in a row, and stock prices are threatened, so they make a move.

It’s important to understand these humans and what’s happening that is making them reach out. By having a relationship with them, you:

It’s important to understand these humans and what’s happening that is making them reach out. By having a relationship with them, you:

- Stay top of mind. They’ll already be thinking of you.

- Build trust, which is essential during an acquisition.

Your Fundraising Valuations Matter

The last thing you want to do as a company is put yourself in a position where you can’t get the offer you want. In general, your valuation is a hard floor on a good acquisition price. Why?

Often, acquirers won’t make an offer below your post-money valuation because they understand the complexities for the board to accept it; offering VCs less than a dollar on their investment is a good way to upset them, and they want relationships with these VCs.

If the offer is below your number, it’s bad news for somebody. If you’re growing like crazy and earn that valuation, and it’s a reasonable multiple on your ARR, take it. Otherwise, you need to stop and think about it.

What if a $100M outcome was great for you, but you’re being offered a $200M valuation? You’d essentially be walking away from a $100M acquisition in that moment.

The Process

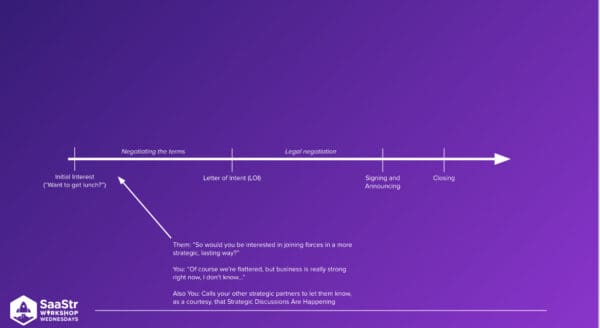

They’ve decided they need to make the splashy move and put this offer down. What happens now? Here’s the timeline from initial interest to closing for Harry: about six months for the entire process.

The Letter of Intent was in late March or early April, toward the end of the process. Initially, you’ll get lunch and get to know each other. Then, you may hear what the offer might look like. It’s much like a term sheet in a fundraiser, but with an LOI, the process becomes exclusive.

Once you sign an LOI, you aren’t engaging in acquisition talks with anyone else, which means they have all the leverage. You want all negotiations done that you care about before you sign the Letter of Intent.

Don’t Give It All Up in the First Meeting

What’s going to happen first is they’ll say something vague, and you’ll say, “I see your point, but we’re growing for the long run.” Don’t give it all up in the first meeting.

Before the LOI, you want to leverage the other relationships you’ve been building. Reach out and tell them that, as a courtesy, you’re letting them know you’ve had some interest and wanted them to hear it from you instead of the media.

If they’re interested, they’ll start running their own internal processes to generate terms. Having multiple offers is the best way to generate a competitive dynamic.

These folks will also talk to each other, so, at that point, even if only the original offerer makes an offer, they’ll notice that you’re shopping it a bit, which creates the perception of a competitive dynamic.

Term Sheets Are Very Different From Letters of Intent

In fundraising, if you get a term sheet and sign it, there are only a few cases where it doesn’t close.

- The VC discovers something in diligence where they think you’re lying to them.

- There’s some foundational shift or big macro market change.

Aside from that, VC term sheets from honorable VCs close. LOIs from acquirers generally don’t close. Harry’s legal team says there’s a 50% close rate, but he guesses it’s even lower than that.

So, as you’re going through an intense process and making peace with potentially losing your baby, know that it will probably fall through. You have to keep running your business as if that will be the outcome.

The other dynamic is exclusivity. You’re about to enter a position where you can’t talk to anyone else about M&A. But also, there’s less than a 50% chance that you’re closing this deal. It’s a tough place to be.

Before you sign a Letter of Intent, make sure:

- It specifies the exact price you’re going to get.

- It says how long you’re going to be exclusive.

- It clarifies any milestones you’re expected to meet.

Don’t sign an LOI that is vaguely worded. An acquirer may say something like, “We trust each other. We’ll figure it out later. Don’t hold up the process. We’re excited!” Take a beat and make them sweat a little. Make sure that what you care about is in writing in the LOI before you sign it.

You will lose almost every negotiation after you sign because lawyers get involved, and theirs are more numerous and better paid.

You Must Keep Running Your Company

Deals can blow up the day they’re supposed to close. If your team is sitting around watching movies all day, thinking about what they will do with their money, you have a problem.

First, you want to make sure only the essential people know about what’s going on during the process. Keep it as close as possible. Once a sense of getting acquired goes around, people stop hitting targets. And if the deal blows up, it could kill your business. It’s happened.

Are You Sure You Want To Do This?

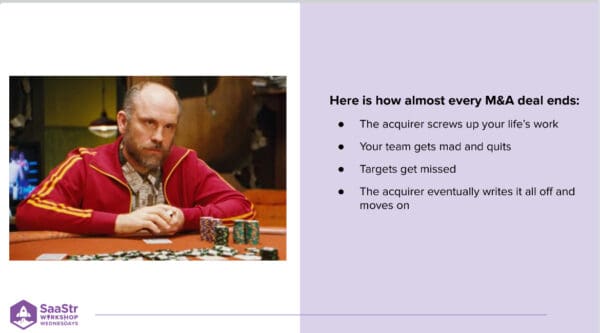

Harry guesses that what happens in about 92% of companies after they get acquired is:

- The acquirer gets their hands on it.

- They try really hard to integrate it and run your business.

- If they trust you, they’ll ask you what they should do.

- Eventually, they trip over themselves trying to execute a business they aren’t familiar with and screw it up.

- Targets start getting missed.

- There are bad feelings on both sides.

- Your baby gets shoved in a corner.

Sometimes, this doesn’t happen. Google’s acquisition of YouTube was awesome. If this slide looks worse than your current situation because your business is going great, maybe you should stick with your current situation.

As a founder, you will have a hard time working for the acquirer. It can feel lonely. You aren’t part of their team, and yours is realizing that they aren’t in a cool startup world anymore. You become a bridge between these two worlds, and it can be a tough couple of years.

It’s a big win, but it’s still hard. Harry doesn’t regret his acquisition but cautions every founder who enters this process that it might look like this.

It’s Your Job to Keep Your Promises

The six months before and after your close date will impact your reputation and the reputation of the founders and senior team. You’ve made promises to your VCs and promises to your employees, and only you will be able to hold up those promises.

The acquirer will propose various mechanisms for not having the VC get their 20% share or for an employee holding 1% to get their share. Stand by your team and your promises. Your reputation hinges on the following:

- Whether you kept your promises.

- Whether you were transparent when it mattered.

- Whether you were empathetic with everyone.

5 Key Takeaways When Selling Your Business

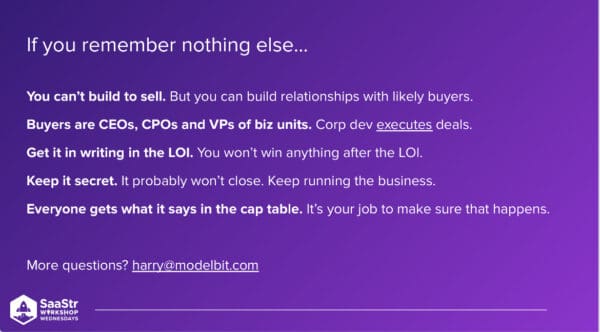

- You can’t build to sell. But you can build relationships with likely buyers.

- Buyers are CEOs, CPOs, and VPs of business units. Corporate development executes deals.

- Get it in writing, always, in the LOI. You won’t win anything after you sign.

- Keep it secret. It probably won’t close. Keep running the business.

- Everyone gets what it says in the cap table. It’s your job to make sure that happens.